32 Mn $ in 2017.

99 Mn $ in 2018.

201 Mn $ in 2019.

The above figures are not revenue figures for a company, but rather funding figures for a sector. They don’t have the large Bn $ cheques, made prolific by Vision Fund earlier, but they represented a growing interest in a rising phenomenon in India, Social Commerce. The latest validation of interest comes with Flipkart’s launch of a social commerce platform. Why is the space so hot?

Let’s talk a walk down the history first.

Commerce has been an intriguing tale in India. 12 Mn kirana shops spread across the country are the pulse of the thriving goods distribution business in the country. They make it accessible for anyone in the country have easy, convenient access to goods. The most traditional behavior for buying goods has thus been to just walk up to the nearest store.

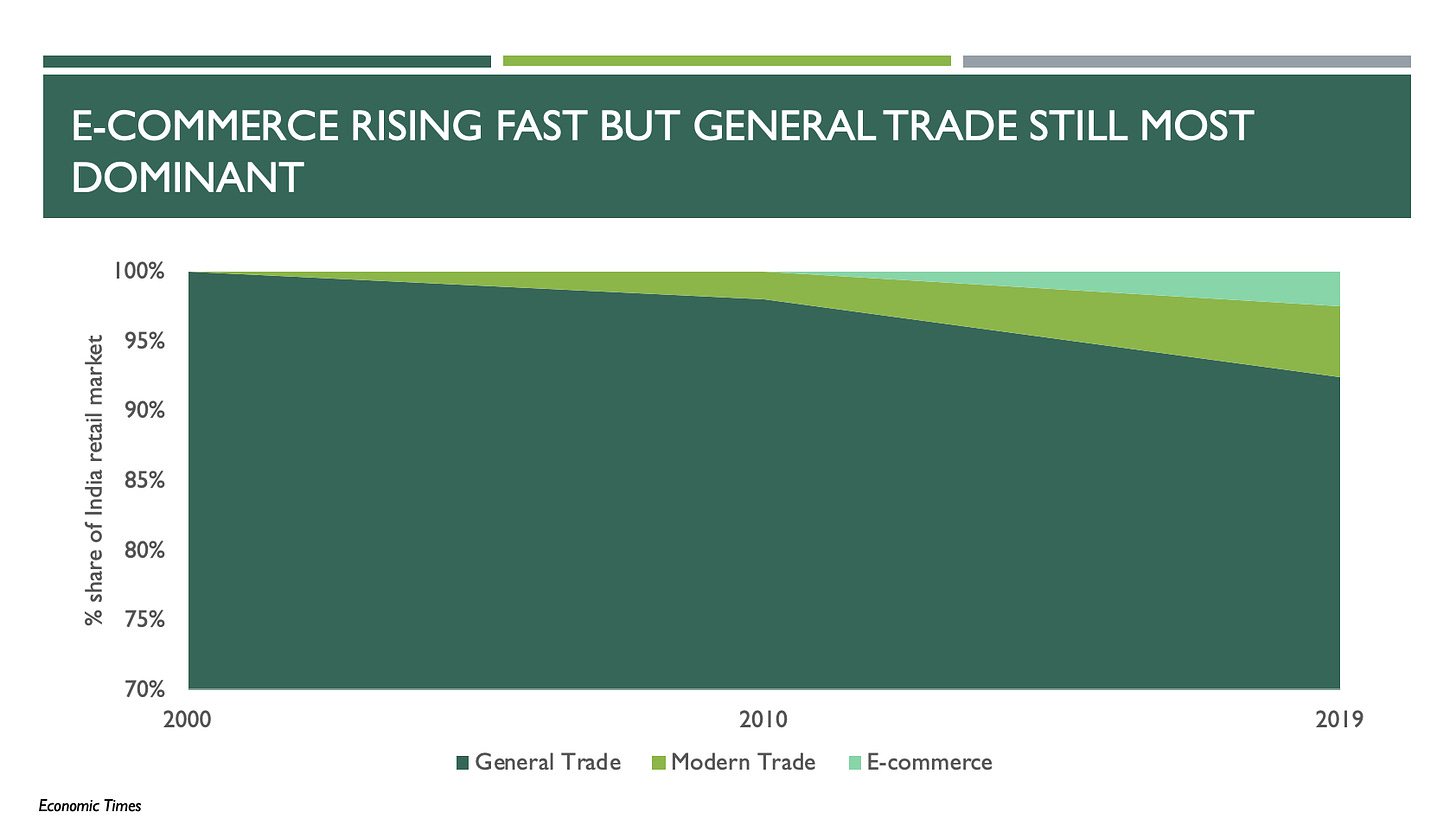

This pattern that stayed for 60 years in the country, started getting disrupted first through a wave of modern retail - Big Bazaars and Reliance Retails of the world in 2000s. And then through ecommerce in 2010s.

This rise of ecommerce, at a 20% CAGR last few years to 20+ Bn $, has been mainly on the back of the likes of biggies like Flipkart, Amazon, Snapdeal and vertical players like BigBasket, Grofers etc.

There are however gaps in the traditional ecommerce model. Over 70% of their business still comes from the more affluent Metro and Tier 1 cities. Purchases are skewed towards branded categories like Electronics, FMCG, Household Appliances, that typically have higher ASPs than unbranded categories. Also, purchases are more search-driven (I know what I want) than discovery-driven (Show me what I should buy) whereas a significant amount of shopping behavior is discovery-led. The last point is also the reason content firms like Instagram are entering shopping and ecommerce through video streaming is increasing.

Enter Social Commerce

India has a tight-knit social community. There are not just strong familial ties but weak ties – neighbors, acquaintances etc. The ties are even stronger in smaller towns. Now, all of the 400 million Indian internet population is on Whatsapp. An enterprising person can leverage this network to aggregate demand across his network, sell common household goods (E.g. kitchen tools, clothes, etc) and earn commissions.

In the traditional commerce, this role is fulfilled by a Class D retailer (the smallest retailer in the chain). However, with easy accessibility of customers over internet, anyone can be a small ‘reseller’ now. In a managed solution offered by the social commerce firms, there are also no additional hassles like managing inventory, logistics or returns. They have to do just one thing – sell.

This is the reseller model that companies like Meesho and Glowroad operate in. Here, the reseller acts as a demand aggregator. There are other models where demand aggregation happens through consumers themselves, through referrals (E.g. Dealshare). Each model, at the core, leverages on the groups formed through Whatsapp, owned by Facebook who also has an 25 Mn $ investment in Meesho.

Let’s pause here and see how social commerce evolved in China through the lens of the biggest company in the space.

PinDuoDuo growth saga

Launched in 2015, PDD has rose to 500+ million monthly active users (MAU) and a valuation of ~100 Bn $. Here’s how PDD works.

To make a purchase via Pinduoduo, shoppers form ‘teams’ and post product listings for their desired items, usually on WeChat. There are referral codes associated with products, that when shared (usually through WeChat) and ordered through, drive the price further down. If your item listing gains an audience, it will appear in more users’ home feeds on WeChat, made possible through PDD’s mini-app on WeChat. This social model, riding on the 1Bn+ users of WeChat, enabled the rise of PDD.

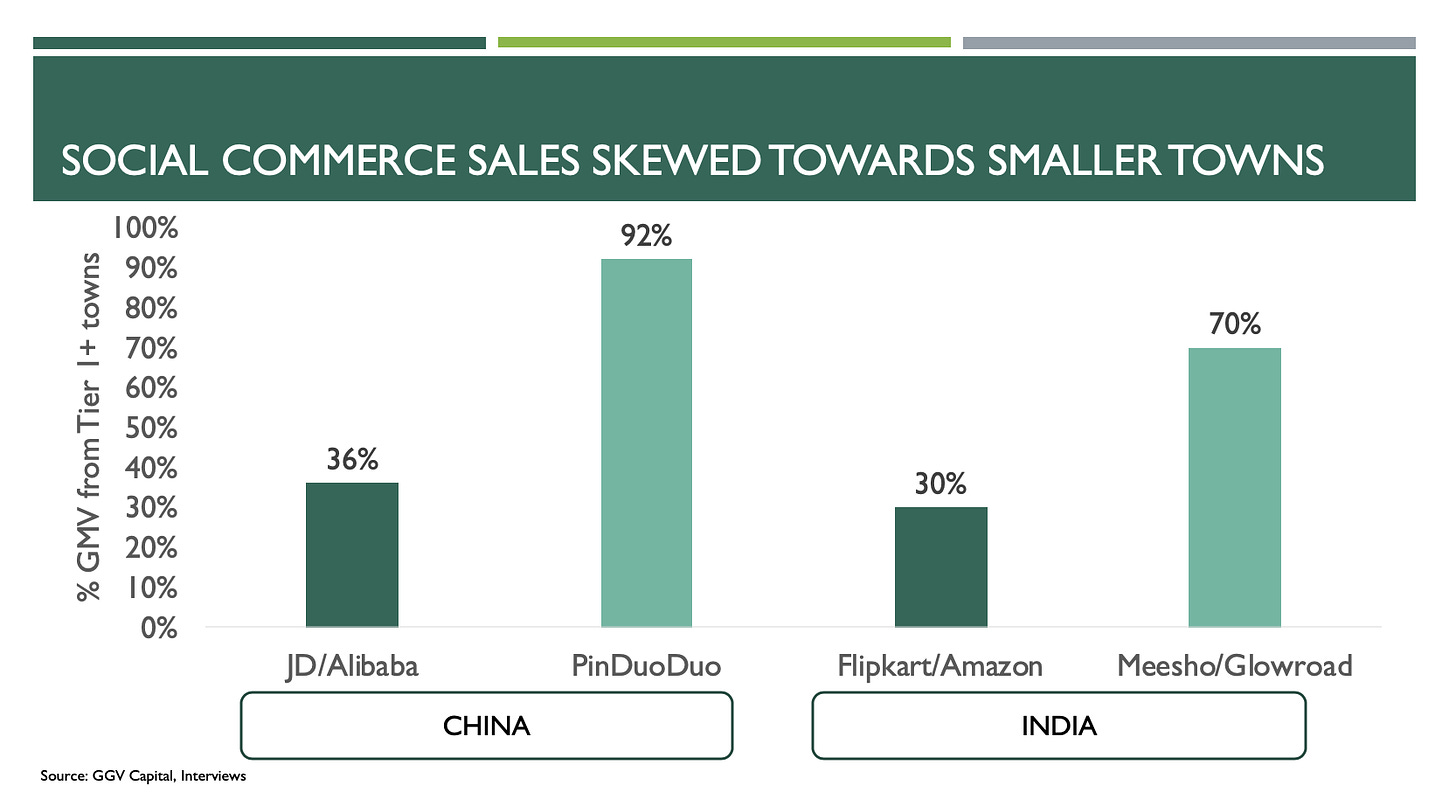

PDD’s presence has been majorly in the hinterlands of China, a stark contrast to the traditional ecommerce sites, Taobao (Alibaba) and JD as shown below.

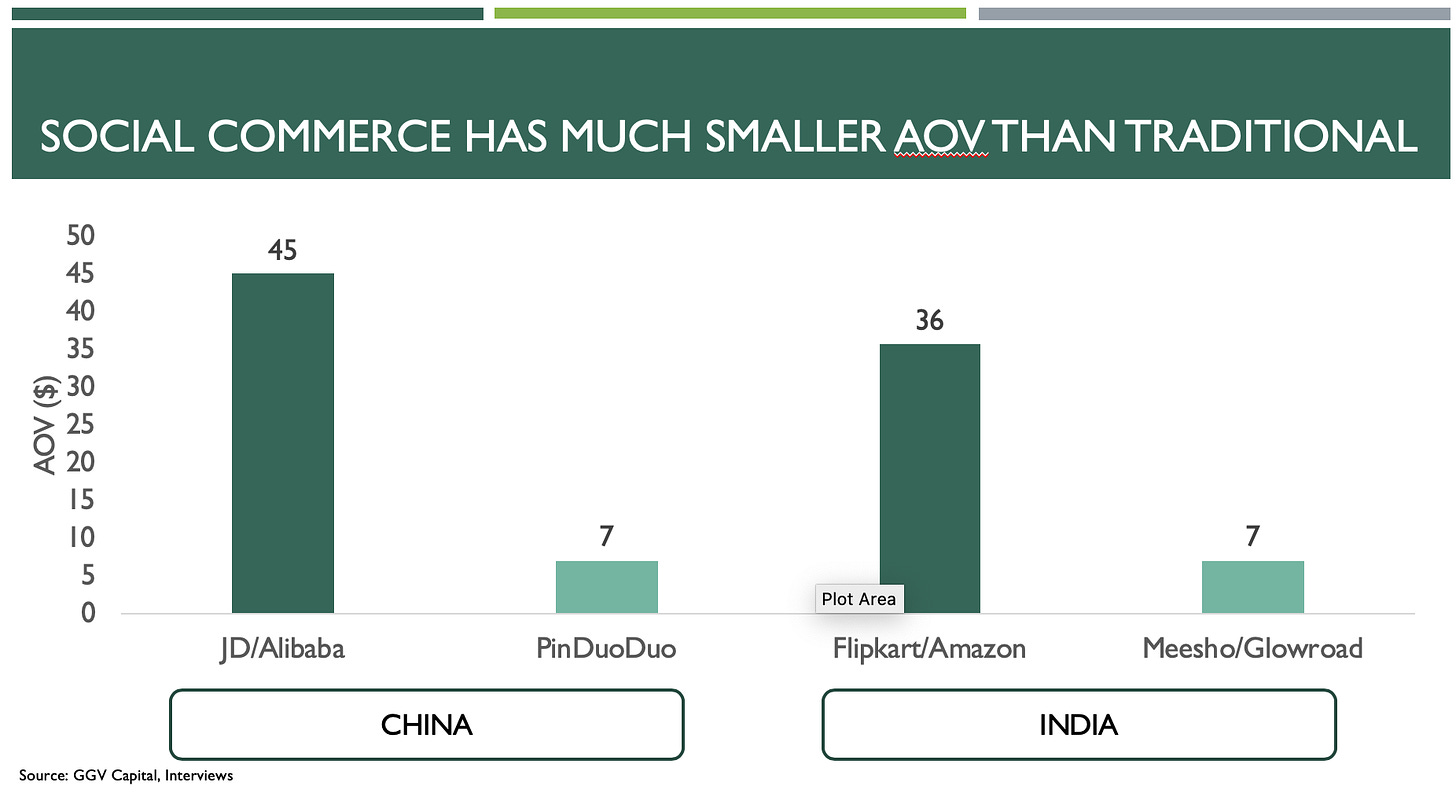

The AOVs are also different.

PDD’s sales hinges a lot towards low ASP, unbranded items, very different from Alibaba and JD that house large brands. And Indian startups are also closely mimicking the patterns. The largest categories in social commerce are fashion and household items.

Meesho has grown to 10+ Mn resellers. Glowroad is not far behind at 6+ Mn. However, while some of the parameters look the same, social commerce in India is a mixed bag, and not exactly PDD.

Companies like Meesho and Glowroad, while they rely on Whatsapp for network, don't have the group-buying element that PDD has. They are hinging on a core motivation of Indians - to make money. The group-buying element is blatant in companies like Dealshare, Wmall, SimSim who rely much more on offering bulk deals.

Do we see social commerce killing it in India, like it did in China?

Thorns on the path

Profitability

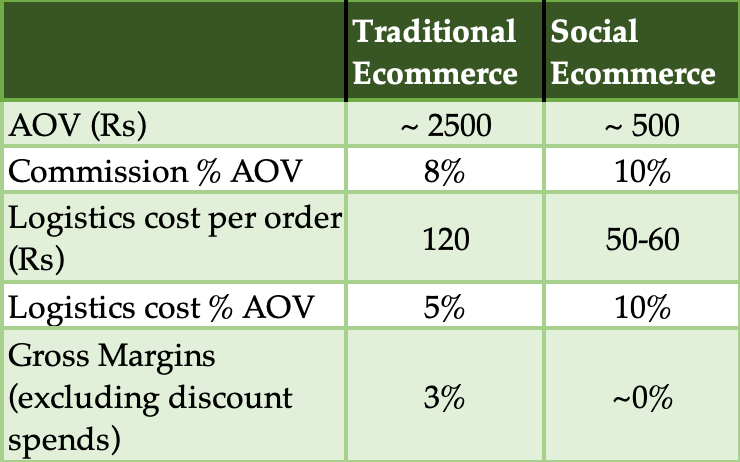

Below is a rough breakdown of profitability between ecommerce and social ecommerce model.

Lower AOVs in social commerce make logistic costs as a % of total higher than traditional ecommerce, since logistics cost have a high fixed cost component. This hurts profitability, until higher spending power leads to higher AOVs. However, India’s GDP per capita is still low (China is 2.4x higher) resulting in a lower spending power.

India has 67% of its population living in rural areas, whereas China has 40% (World Bank). With a higher geographical dispersion in India vs China, the logistics costs for reaching last mile is also higher in India, and that also affects profitability.

Whatsapp vs WeChat

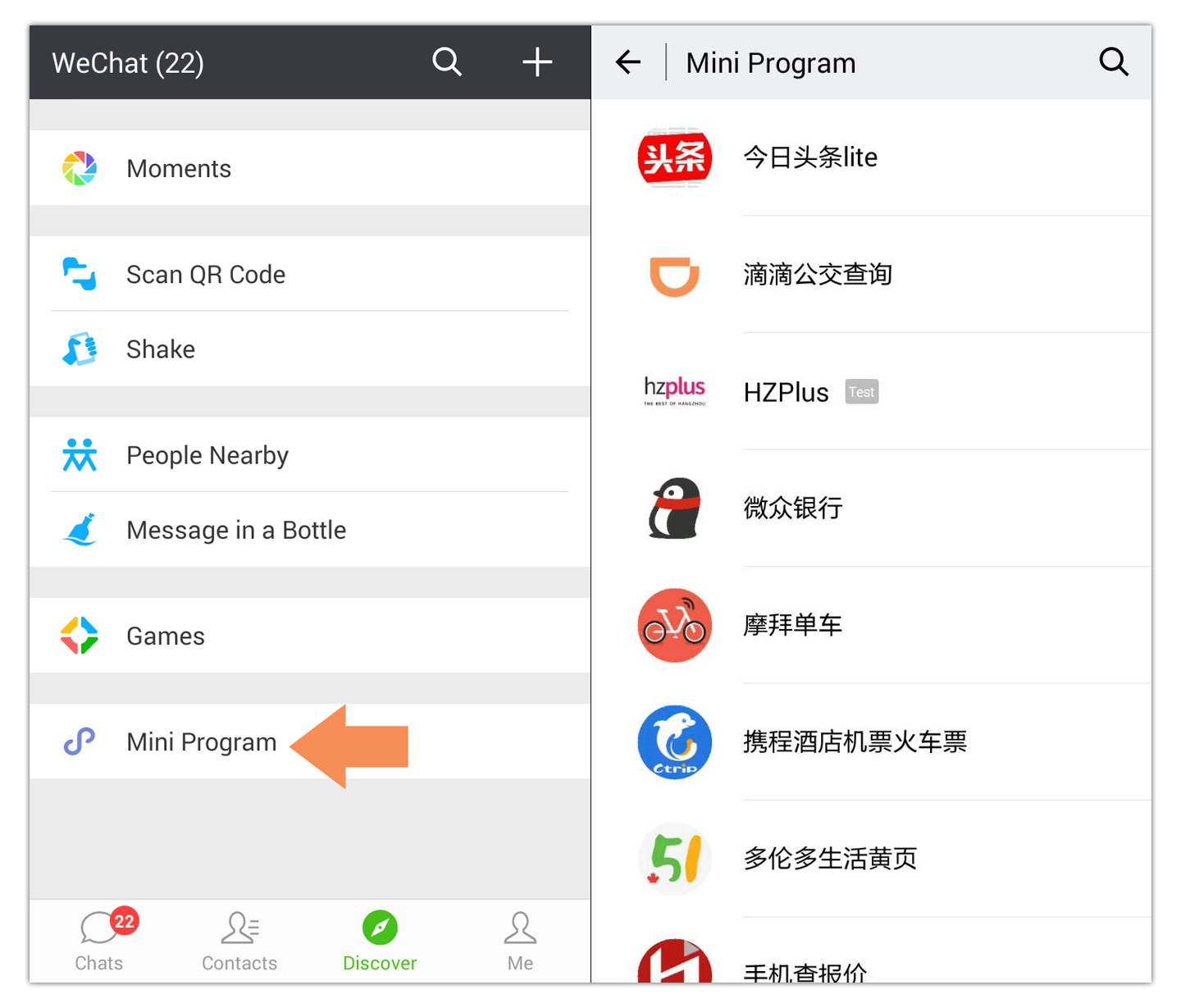

For the uninitiated, WeChat has a feature called Mini-programs that are basically apps inside WeChat. Using this, you can use the third-party apps’ functionalities from within WeChat itself.

This results in a seamless and customized experience for all users. It’s the same as accessing the third-party app, without the friction of opening it separately. WeChat mini programs are so popular that 62% of PDD’s users order through them.

In comparison, the messaging network of unanimous choice is Whatsapp. So far, Whatsapp product choices have been hinged on simplicity, staying only a messaging platform and nothing else. This, however, prevents the customizations that WeChat apps could bring.

Women as a working demographic

21% women are employed in the formal labor force in India vs 60% in China owing to a huge cultural factor against women employment in India. That factor is still strong in the rural parts of the country, where most women are either employed informally in agriculture or are limited to household chores. 70% of PDD’s users are women – and they fuel this engine of social commerce in China with their enterprise among their social networks. Most resellers in India in the social commerce model have also been women albeit mainly from Tier 1 and 2 towns. This industry provides a ray of hope of financial independence for women, specially for Tier 2+ towns, if the cultural bias is overcome.

Capital

In order to weather the obstacles above, there is an upfront capital investment required that will help fund the negative margins initially. Ecommerce has had a lot of martyrs earlier owing to lack of capital. This is also the reason Flipkart, with its Walmart coffers, is making a bet in this space.

No mention of capital these days goes without the mention of Jio, with its coffers piling up from all marquee companies and investors. The most interesting in this line-up has been Facebook. Jio is making its ecommerce play in the country and Facebook owns Whatsapp, the largest social network in the country. Connect the two and viola! You get social commerce.

It might be too soon to predict though how Jio approaches this space. The buzz in the social commerce bottle is not unwarranted. But it remains to be seen whether it stays and gives the returns it has promised.

If you liked this article, subscribe to my newsletter to get such articles in your inbox every month. No spam ever. Leave a comment for any feedback, it’s literally Day 1.